Web Tutorials

HTML, CSS, JavaScript - The Frontend Building Blocks

HTML

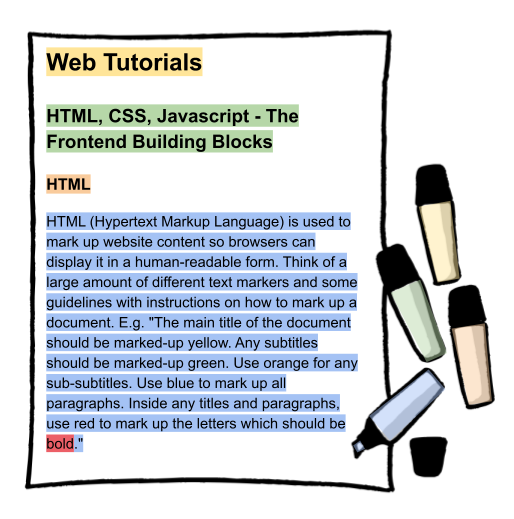

HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) is used to mark up website content so browsers can display it in a human-readable form. Think of a large amount of different text markers and some guidelines with instructions on how to mark up a document. E.g. "The main title of the document should be marked-up yellow. Any subtitles should be marked-up green. Use orange for any sub-subtitles. Use blue to mark up all paragraphs. Inside any titles and paragraphs, use red to mark up the letters which should be bold."

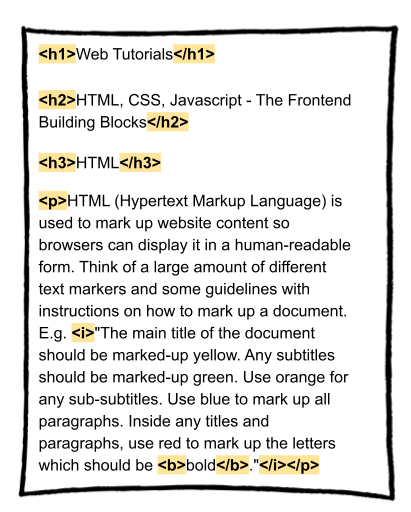

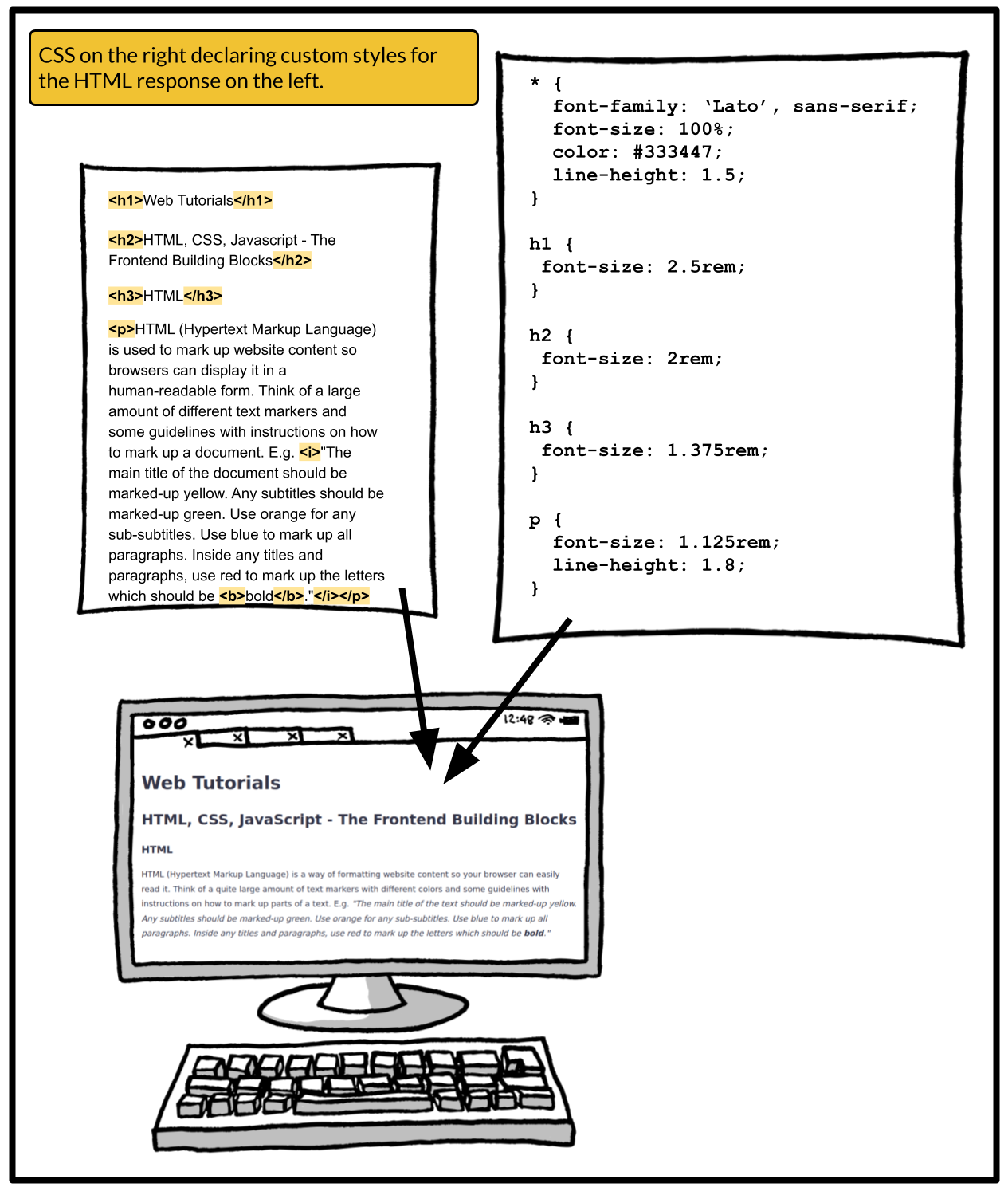

Instead of text markers, HTML makes use of HTML tags. An HTML tag has a name (instead of a color) to indicate what is being marked up. There’s an opening tag and an ending tag to wrap parts of a text in order to indicate where the markup starts and ends. There's also a guideline on which tags to use for which parts of a text. E.g. the main title of a text should be wrapped in a h1 tag (h1 for heading 1). Any subtitles should be wrapped in h2 tags. Sub-subtitles go into h3 tags, etc. Paragraphs are wrapped inside p tags and letters which should be bold are wrapped inside b tags. There are many more tags available, of course. In the image below you can also see an i tag for italic.

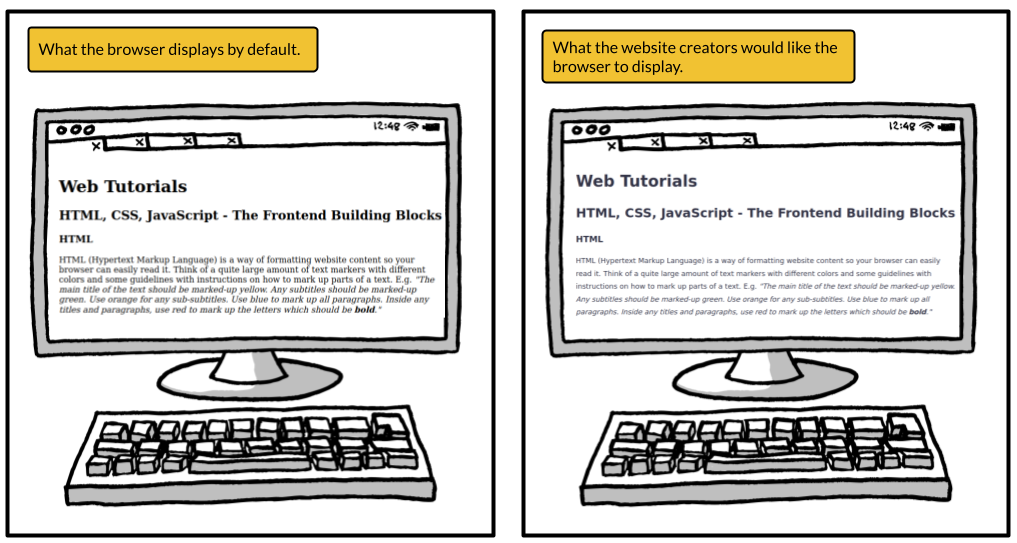

When displaying an HTML response, browsers take care of not showing you any of the actual tags but they consider them by the use of default styles. For any text inside an h1 tag, browsers will use a bigger font. For paragraphs (p tag), they will add some spacing before and after the marked up text, etc. However, website creators might not want the browsers to apply their default stylings. Maybe they want to see different spacings between paragraphs and different font sizes for titles.

Such custom styles are achieved by introducing CSS (cascading style sheets).

CSS

Styles declared in CSS are part of the additional resources your browser might request when you access a URL. So, the initial HTML response probably lists at least one CSS resource declaring the custom styles for this current HTML response. In its simplest form, CSS lets you write down the names of the HTML tags and declare custom styles for these, overriding the browser's default ones. There is much, much more to CSS than this simple approach but this should be enough to get the idea. Just keep in mind that any CSS is tightly bound to an HTML response. CSS requested in the context of one response has no effect on the styles of another one, unless they are referencing the exact same CSS.

While accessing the URL of this tutorial, the HTML response also listed some CSS as one of the additional resources to be requested by your browser. The CSS instructs your browser to override its default styles by applying a different font, using a very dark greyish blue as the text color, using different font sizes for titles, and applying different line heights for titles and paragraphs. Don't worry about the details of CSS syntax. Just be aware that any CSS goes hand in hand with a corresponding HTML document.

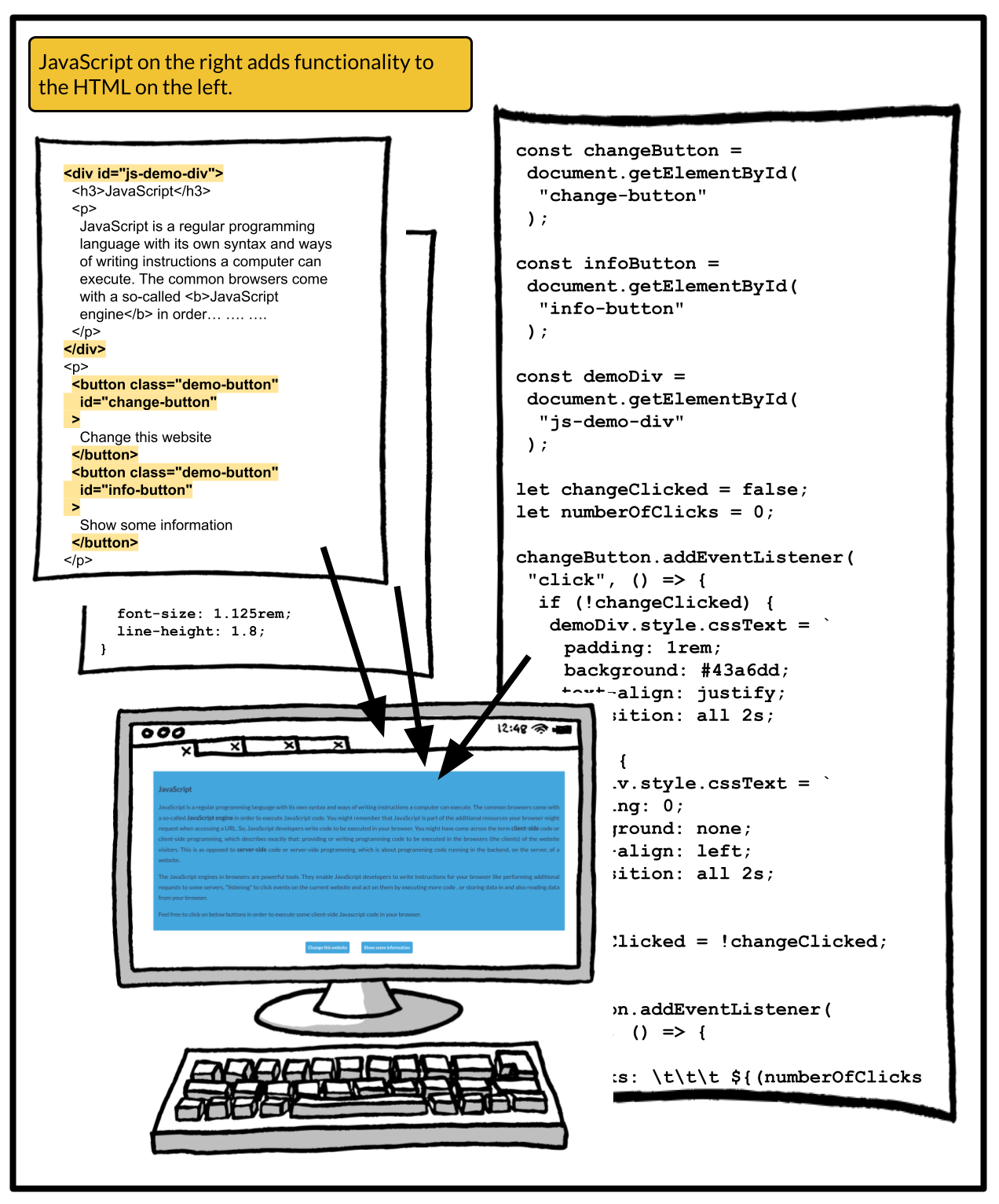

On most websites you have some user experience in the form of interactions. Maybe you click a button and some additional elements are loaded to the website. Maybe you get notified that you missed entering some crucial information when trying to check out and order something online. The changes of the website usually happen without a reload of the website or the requests of new HTML and stylings - it's really just parts of the website that change. This website experience you are so used to is achieved through the use of JavaScript.

JavaScript

JavaScript is a regular programming language with its own syntax and ways of writing instructions a computer can execute. The common browsers come with a so-called JavaScript engine and JavaScript runtime in order to execute JavaScript code. Remember that JavaScript is part of the additional resources your browser might request when accessing a URL. So, JavaScript developers write code to be executed in your browser. You might have come across the term client-side code or client-side programming, which describes exactly that: providing or writing programming code to be executed in the browsers (the clients) of the website visitors. This is as opposed to server-side code or server-side programming, which is about programming code running in the backend, on the server, of a website.

The JavaScript runtimes in browsers are powerful tools. They enable JavaScript developers to write instructions for your browser like performing additional requests to some servers, "listening" to click events on the current website and act on them by executing more code , or storing data in and also reading data from your browser.

Feel free to click on below buttons in order to execute some client-side Javascript code in your browser.

While accessing the URL of this tutorial, the HTML response also listed some JavaScript code as one of the additional resources to be requested by your browser. The code instructs your browser to "listen" to clicks on each of the above two buttons and to execute corresponding code when a click happens. You don't need to understand JavaScript syntax but I hope you now have an idea of client-side JavaScript code and its powerful role in your website experiences.